|

| Photo: Facebook |

"What's kept me going is the technology. I love the technology. And the changes. I really embrace that." - Richard Mitchell

One of the key South African engineers and producers of the 1980s, Richard Mitchell passed away on 8 December 2021. The following is a transcription of an interview with him at his home in Johannesburg on 16 November 2009. It has been edited for clarity.

(How did you get started in music production?)

I started in Cape Town. I was actually born in Zimbabwe, left when I was 6 months old. We traveled all over the world, South America… then came back and finished school in Cape Town.

I started as an assistant engineer in Cape Town, and one of the first sessions I worked on was ‘Mannenberg’ with – it was DOLLAR BRAND in those days. And I think that was probably something that just sealed my fate. We did four or five day and nights of us recording, and that as just one of the tracks. It was a studio called UCA. It moved it’s now Milestone… Murray Anderson. But I think it was in a different building that time.

I came up (to Joburg), late 70s. I actually came up with a band called BALLYHOO. The whole idea was that we were going to set up a studio in Joburg. I’d been doing some work with them down in Cape Town. And that didn’t work out. So I ended up at a place which is now the AudioLab, in Blairgowrie. It was part of the Teal Record Company in those days, which became part of Gallo.

(Did you ever play in any bands?)

No I was a shocking guitar player, in university. I was really terrible. I was studying marine biology. So I think I realised that very early there was no way I was going to (make it as a musician).

(How did you become an engineer, were there courses to study?)

No there weren’t any. You could join the SABC. (but) I had a British passport so they refused to even accept me. Some of the guys went to courses overseas. I was lucky, I was taught by JOHN LINDEMANN, he was kind of in a way my mentor, a highly respected engineer. But it was a hard road. It was the typical kind of …(being the) the teaboy, and running around, and then you get thrown into the deep end - and sink or swim. I was working doing radio commercials at the studio. And John was the chief engineer, and left. And recommended me. He was more into studio management at that stage. He oversaw a lot of what was happening.

(What was producing an album like during the 80s?)

We sort of hit a formula almost, I did a huge amount of work with ATTIE VAN WYK, we did all the YVONNE CHAKA CHAKA stuff. And we co-wrote a couple of things together. The irony of it was that we did a lot of it in a little mobile studio, parked in downtown Doornfontein. It had a sort of studio room attached to it… It was all programmed, drums and stuff. But we would sort of knock out a tune in a day, go away and have an idea of lyrics. His wife used to write quite a lot as well, and we’d sort of pool all our ideas together.

(Synths became a central part of the sound – why do you think this was?)

It was just something that was really working. The early CHICCO days, and Yvonne – that sort of poppy groove, it almost followed on from the HARARI, the band era. And I think it became…It was obviously a more affordable way of achieving certain things.

(Was the American influence on bubblegum overt or more subtle?)

Obviously some of the influences were from America, but I think that was actually more in the late 70s, with the Kool & the Gang – and the groove kind of stuff. This almost – the groove content of it was actually almost new. It was really based around the pantsula guys, and their dance kinda style. Very much an offbeat rhythm, snare drums and all that kinda stuff. So it really wasn’t following anything from the international side. The melody side was very – almost European pop, in a way. And I think that was what interesting me about it, was that it was kind of rhythmically very African – well kind of African, in a way – but very new. But then the pop melodies - especially ‘cos Attie is a very prolific writer, as such. With just straight-ahead pop melodies put across it.

(Was there any live instrumentation?)

We used some live instrumentation. But predominantly – the drums were all done on LinnDrums, and things like that. It was a learning curve. Everything was still tape-based, so everything had to be sync’d up … (And there were) various codes. I used to have nightmares with codes.

(How much input did the artists have in songwriting?)

To a degree, a fair amount. Yvonne liked to contribute, more and more actually as she got more confident. Chicco also used to contribute an enormous amount.

At that point I had worked a lot – sort of mid-80s, had worked a lot at RPM studios, which was part of the Teal – was merged in with RPM studios, which is now Downtown studios. And did a lot of stuff there till the mid-80s, then (I) had gone, said ‘OK, now I’m a freelancer,’ and set up my own company.

And it was interesting, because I was actually working with EMI and with an offshoot of Gallo, Dephon. So I was doing Yvonne, plus we were doing BRENDA FASSIE’s stuff as well, and CHEEK TO CHEEK, and all that stuff ... It caused an interesting [tension between] Brenda and Yvonne – ‘You gotta work with me, you can’t work with her!’ But it was an excited period. Things were going out there and selling copious amounts.

I think it [competition/rivalry between Brenda & Yvonne] was quite healthy. And it was interesting that in the end, CHICCO ended up producing some of Brenda’s biggest hits, from ‘Too Late for Mama’. But I mean he’d also done quite a lot of work with Yvonne. I’m not sure of his exact details, but I think his mom ran a shebeen and was a really street-smart kid. And he was a percussionist in one of the offshoots of HARARI, UMOJA. But rhythmically he just had something - he was unbelievable. He had the ability to hear something and adapt it. He’d probably shoot me for saying this, but he heard Simply Red, and adapted that into a massive hit, it was called ‘I Need Some Money’. He knew how to lock down a groove. He’d take grooves that we’d programmed, and he’d go away and come back and say, ‘No, this is wrong, that’s wrong, change this.’

He knew what he wanted, and he was also part of the Dephon stable at that stage. He started as a percussionist, then as a solo artist. He had a smash hit singled called “We can dance”. He eventually evolved into production. Its like any artist, they want their ideas…

(What was is like working in the context of international isolation & the cultural boycott?)

It was an interesting period because fundamentally there was such a boycott going on with the international artists that there wasn’t a huge amount of content available. And that’s why the local industry boomed. It was probably the most prolific period. Because people were looking for music. and they couldn’t buy the new U2s. There was (only) some (foreign stuff)…

(Was the music industry segregated, or how did artists cross over?)

I think it was quite targeted. I don’t think it was a kind of conscious sort of thing. It just happened. There was some kind of crossover. Like I remember some of the CHICCO songs would be played on 5FM, or Radio 5 in those days. There was a fair amount. Guys like Alex Jay were phenomenal with picking up on some of the local, almost more obscure – huge hits that were happening in the townships, and kind of bringing them out (to whites).

But I think also in the studios, it was almost like a breakdown of apartheid. It had been happening over a period of time, where there was a lot more interaction between white and black musicians and things like that. So there was a lot more respect from both sides, of what was available.

I did a band called eVOID – ‘Taximan’ was actually played by BAKITHI KHUMALO, the black bass player, which nobody knows about … It was Erik and Lucien [Windrich] … Erik – he used to play bass and the keyboard, but he didn’t really have the chops to play it accurately enough. So I said, ‘I’ve got a bass player for you’ and I got Bakithi. And that goes way back, we used to do that in the 70s.

(Outside of the studio, were mixed band playing live too?)

I think in that era there were more mixed race bands. I think JOHNNY CLEGG was starting to happen.

I mean that was ’84, ‘85 – there was the big Operation Hunger CONCERT IN THE PARK – there were over 120,000 people there, at Ellis Park. They reckon it was probably more. As a concert it was phenomenal, because it was such a crossover of everybody, from HOTLINE and JOHNNY CLEGG and STIMELA to white pop bands

What was interesting at the time was that a lot of the music was sequenced and programmed, but they would go out with bands and play (live). It was just too difficult at that stage to get the technology to go out (instruments belonged in the studio).

For anybody in the music industry, it [Concert in the Park] was one of those milestones – ‘OK, we are finally breaking down the barriers.’ I think in fact [US Senator] Edward Kennedy was in the country at the time. and I remember it because somebody stood up and said ‘Edward Kennedy should come and see – this is the future of South Africa’. And it was one of those really (powerful moments), I think it was RAY PHIRI, or CLEGG or somebody. And I just thought it was one of the most profound statements. It was so true.

(People could begin to see of the end of apartheid?)

Ja, it was around that time there was that whole Rubicon speech. We all expected [president PW] Botha to back down and say ‘OK, that’s the end of it’, and he didn’t - that sort of prolonged and dragged it on.

I think it had actually got to a stage when people had really had enough, and were a lot more vocal about it.

(Were people of different races socialising after-hours?)

It started … I mean the 80s was an exciting period because we started actually hanging out a lot together. There was a club in Sebokeng called Easy By Night, that almost became our- the music industry hang out. STIMELA were known there, STEVE KEKANA, all these kinds of people. We used to all go and hang out, and we’d take more and more people. So it was kind of a fun place to go. I remember the first couple of times being really kind of embarrassed – 'cos I mean we’d arrive, and jump this whole long queue that went halfway round the block. And everyone looks at you, you go ‘oh my goodness’ (embarrassed), but it was cool … It was just a really fun period.

(Any bad experiences?)

I don’t remember being in a (bad situation)… there were odd festivals that got aggressive. A lot of the time that was because there were bands didn’t arrive and all that kind of stuff, things would go wrong. But in the early periods, it was almost like this release, of tension and stress. It was an explosion actually, a cultural explosion. People wanted to go and hear this music they’d been hearing on the radio.

(How did you deal with censorship at the SABC?)

I think we started to get more of a ‘fuck you’ attitude, you know. I mean there were songs being banned left right and centre. Some of the STIMELA stuff was banned. What they used to do is take a styluses and across that track, gouge it so you couldn’t play it on the vinyl. They kept trying to keep thef lid on it ...

YVONNE not so much, because she was more mainstream pop, but I mean BRENDA certainly started pushing the envelope. I mean you look at ‘Too Late for Mama’ and ‘Black president’. ‘Too Late for Mama’ is actually an indictment of the society – the sadness of this lonely woman. It was the late 80s, about ‘87,’88, (so by then) I think it (apartheid) had probably had it. I think everybody was kind of anticipating that the end was close. I mean we did a release when Desmond Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize, that was in the 80s (1985). It was a collaboration with SIPHO GUMEDE and RAY (PHIRI) and a whole bunch of people… It was never released here, it was smuggled out of the country and released in the states.

(Was other SA music getting outside the country at the time?)

A fair amount. Look, you know, there were two sides. There was the political undertone, but there was also the straight ‘let’s do pop music and avoid that [politics]’. And obviously some of the more serious musicians were a little bit disparaging about the pop music.

The jazz guys – the Stimelas and all sorts of people like that – there was an enormous amount of, I wouldn’t call it piracy but copyright infringement – people would listen to each other’s music and rip it off, adapt it and stuff like that. Whoever came up with a new kind of hit groove or whatever, there would be ten permutations in a couple of weeks.

(What role did Stimela play?)

The interesting side to the whole thing was that STIMELA were signed to Gallo, but Gallo didn’t want to record them. They didn’t think that their music would sell … Stimela was actually formed from two bands that were like under the Gallo label, it was THE MOVERS and THE CANNIBALS. And they had been doing a lot of kind of American-style groove stuff, and things like that. They fused and they started recording with different record companies, under different names. What they’d do is find frontline guys, and that’s how bands like the STREET KIDS were formed. That was really all RAY and the Stimela guys. They started programming stuff - ‘Game No.1’ and all that. Some of it was live, some of it was programmed. That’s when the serious guys started to see what the technology could do, as well.

(Didn’t this cause contractual headaches etc?)

Oh ja no (yes), there was. They [Gallo] tried stop them. Eventually they just relented and said, ‘OK, we’ll record you’, because hits were popping up all over the place. And they suddenly woke up to the fact that ‘these are our guys’. But they hadn’t tied some of them to production contracts, so they missed out on that one. But the reason I brought them in was it was interesting how they started using the new technology as well, and embracing it.

(Was there competition among engineers/producers?)

I think everybody was out to kind of achieve what they could. It was an interesting period because we were trying to push the envelope all the time - and everybody was convinced that what they were doing was the best thing since sliced bread. But so much of it, if you look back at it, all had a similar sound. It became passé in the end because everybody kept going to those clichéd sounds. But in the initial stages, with the Yamaha DX7 and things like that, they were phenomenal sounds. This was like, wow! And then we became adept at actually being able to programme and I think engineers - the successful ones - became really good programmers at the same time. You had to.

(How did you cope with the rapid changes and innovation in technology?)

You had to learn on the job. There was no period to sit back and (research/practise)… and it became a standing joke: who has the time to read the manual? You just get in and do it!

(How regularly could one churn out albums - weekly?)

It would be, ja, just about (weekly). Maybe a bit longer, 10 days, two weeks max.

(So you were always in the studio?).

Ja, I was a workaholic for about 4 years, just 24 hours a day.

(But if you love music…) Ja, it was a fantastic period.

(Did you consider it work?) No. You know, for me, the greatest satisfaction was actually – when I used to work at Downtown Studios, we’d walk up to the Carlton Centre, and go past all the taxi guys and hear songs that you were working on, blaring out while they were washing their taxis. It was a heck of a kick, that whole mass communication thing.

And then going to festivals and seeing that songs a lot of the time badly translated by bands. The bands of the artists, they were desperately trying to play [the programmed stuff], which was kind of impossible, you know.

(No backtracks?) No, it wasn’t even considered. The biggest problem – you know the keyboard stuff and that – was one thing, but it was the drum loops and all that kinda stuff that they battled with. And I mean eventually you ended up with sometimes – I’m trying to remember the name of the group, I think Cheek To Cheek or one of the Gallo artists – I mean they had six keyboard players on that stage! (Each) just doing one thing or the other, because you’d just layer loads and loads of the stuff.

(What was it like working with Mally Watson and Attie van Wyk?)

With Malcolm I was just an engineer … Malcolm was phenomenal. He was probably one of the most disciplined musicians I’ve ever come across. And I mean that in a big complimentary way. He always had his stuff pre-programmed well. He knew what he wanted. It was always a pleasure working with him. It was the easiest. For me it was a huge compliment. It was an interesting period, because that was when I had left the Gallo group, and I was a director at RPM studios, and just said ‘enough’. I was working as an engineer, I was the chief engineer, but I was made the director, I think to keep me quiet. But I left, I said ‘no’, I went to freelance. And Malcolm immediately picked up the phone and said ‘do you want to come and work here’? I said ‘great’.

So I was working with Attie, and with Malcolm. They were at the stage probably two of the (best) producers (in SA). So I’d do a day with one of them, then I’d go and do a night session with the other.

It’s a collaboration. The producer is somebody who normally will take the project from A to Z. An engineer will come in and in those days the engineer’s role was kind of more – obviously there was a whole lot of technical areas, with tape machines and mixing consoles (so you need more than one person).

With Malcolm, he’d pretty much mapped out the songs in preproduction. That’s why I say he was really organised. He’d do a lot of that. With Attie, he and I would sit and actually write all the programming. They both came from enormous musical backgrounds. I mean Malcolm was one of the top session players.

Attie and Malcolm ... there were other guys involved. And I think that the interesting side – they were two white guys who were doing it … I think eventually that wore a bit thin.

(Why was it often white engineers & producers in studio with black artists?)

I think of lot of it was just that they were coming up with the popular melody lines. The black guys were coming up with the grooves, and the rhythmic side of it, but the lyrics and melodic structures (were done by whites). And I think that’s where the thing took off. Because before that, it was kind of all OK but it was just really amateurish. And all of a sudden we’re hearing, like, the ‘Weekend Special’s – you know, timeless melody lines.

An interesting anecdote with YVONNE was that ‘Umqombothi’ which has become her signature tune, was done on a Monday morning. We started missing around with a cassette of some groove that Phil (Hollis) had found. Or no it hadn’t… the track he wanted us to kind of copy and adapt or whatever hadn’t arrived, so we started messing around. And Yvonne was there, and wrote this, kind of composed this tune. And (it was) Attie, AL ETTO, myself and Yvonne. And Phil came in later in the afternoon and listened to it, and said, ‘No, that’s rubbish - absolute rubbish. It’ll never sell!”

I mean the grooves were quite extensively researched. It was a lot of time … especially with Chicco, he used to spend an enormous amount of time working on a groove. I mean he’d take a groove and go and play it in a club at night, and see if people reacted to it. it was all about the groove and the bassline. And once that was locked down. You see, that’s where the guys like Malcolm and Attie were good. They’d take that and then put some nice chord changes, verse and chorus structures and so on… Before that, it was just this endless, repetitive groove.

(How did lyrics come about?)

You’d try and come up with some kind of concept for the song. And then write a rhyme around it. But it certainly wasn’t a case of lyric first, and then melody… (groove was main thing). And I think even today, a lot of it is like that. It hasn’t changed that much.

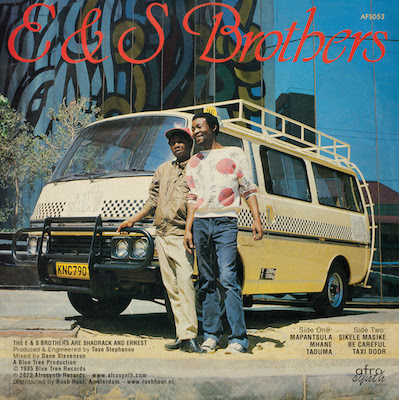

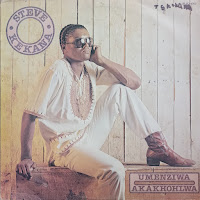

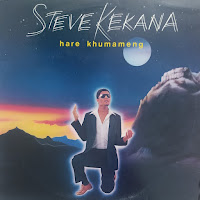

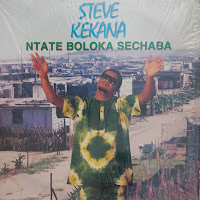

(What was it like working with Steve Kekana?)

Ken Haycock was the MD was CCP Records, which was the black division at EMI. Ken was phenomenal. My fondest memory with Ken was I’d done an English album with STEVE KEKANA. We wrote all the tracks, and he said, ‘you guys go have some fun”. I don’t know where they come up with the song - ’The Bushman’. And it became this (hit). Technically it was a huge amount of fun, because it integrated drum machines and live drummers… it was a melting pot, cos I’d worked at VideoSound, and they were doing Gods Must be Crazy. I phoned the director and said ‘can we have access to some of the Bushman stuff?’ So the guy in the (song), the bushman, is the genuine guy from the Gods Must be Crazy. It become this big, massive crossover hit.

He (Kekana) was the most phenomenal singer. He was just a singing machine. I mean it was frightening what he used to do. He’d just go in and sing and sing and sing. And do all the harmonies and just track them, and it became this huge sort of synthesized voice sound. Everything was … vibrato .. everything was just perfectly matched. It was frightening. And he was such a great human being. I did stuff with Malcolm with him, I did stuff with Tom Vuma, who did a lot more indigenous African stuff, earlier on. And then we did an album… Steve went to Gallo and we did an album. The Stimela guys actually played on it. I just remember because the sleeve was phenomenal, the guys were all in dustbin outfits…

The problem is that most of the black music in those days was not given a huge amount of credit. A lot of the deals that were done were extremely dodgy. People were handed recording contracts, with a publishing contract kinda tucked in, and they’d just sign away (their rights). It got better (in 80s), but…

(Some black artists must’ve been making money though, right?)

They were, but by the same token, the record companies were creaming it. so … if we looked at the deals today, there’d be different structures in place. There were…especially young, up-and-coming people were kind of cajoled into signing deals that were not that kosher.

(Any memories of working on Sipho Hotstix Mabuse’s hit BURNOUT?)

We’d done another version of the song. And this conversation came up. Sipho was playing around with the piano one day. And I recorded it, put in on (tape) and said, ‘That’s a great lick, we should do something with that.’ And he went away. I’d just got a LinnDrum - that day, or the day before. And I was playing around - how did this thing work? (I found) it’s got a rolling tom pattern in it, and thought ‘oh, that’s really cool, but it should be doing this…’ And that’s how the song (started).

And then he went in and played the piano lick. Steve Kekana actually came in, he’d been out partying with some friends and wanted to show them the studio. I said to him ‘come and sing on this’. He said ‘No, I can’t’. He went away, dropped his friends off, he came back and said, ‘This song has been going in my head, I want to sing on it’. and that’s how it happened. It was a bizarre situation (coincidence). And that was the time….

What happened was that Gallo heard the song, and heard the potential in it and said, ‘Forget the rest of the album, we’ve got enough, don’t worry. You’re taking too long.’ It was the first 4-track album that came out.

(When did the bubblegum era start to slow down?)

I found eventually I started to get very bored with it. I think probably for me, one of the turning points was when one of the heads at one of the independent record companies came in with a cassette of an artist I had just finished co-producing, it was a pre-release copy that he’d managed to get hold of. He said, ‘This is what we need to copy. This is gonna be huge!’ He didn’t know [that RM was the one who did it]. I just thought, ‘No, this is starting to feed back on itself.’

(When was this?)

Probably late 80s, I think. And that’s kind of when it started changing … CHICCO became more aggressive in a way, almost militant, in his lyrics and things like that. I think we started to incorporate more and more live instruments into it. There always had been the live (element)… the drums tracks were programmed, but the bass player would play live, or the guitar players, or stuff like that.

I think people were buying less but they were also buying slightly different ... it was more international, and a lot more of the kind of higher-level musicianship - the STIMELAs really started to blossom.

I think the labels started to make less money. From my point of view, I started, as I said, to get bored... I think I probably made that apparent to Attie and Malcolm. For me, I think once we’d done ‘Too Late for Mama’ with Chicco (producing), then I did the follow-up album, which had ‘Black President’ on, but the rest (of the album) didn’t really have anything (special) on it.

I started doing an enormous amount of film work then at that stage. There was a period when there were big tax concessions for movies being shot in this country, so (there were some) huge soundtracks being done, or fairly big soundtracks. A lot of that, in the late 80s. I did some stuff with Katinka Heyns. And then.. I did a very interesting movie with a guy called Jeremy Lubbock, who was an ex-south African guy who’d done the “Nuts” soundtrack with Barbara Streisand (and) who worked with Michael Jackson. He was a guy who had been living in LA and was known as an orchestrator.

So I think I’d sort of moved on and said ‘OK, time for change’. I was doing quite a lot of stuff with Ray at that point. He had done the GRACELAND thing and people had picked up on him. He was doing a lot of demos that were picked up by a French record company. But then he went out on tour with Graceland, I think for 18 months, and they kind of lost interest.

(Any more thoughts on Graceland?)

I think there were some issues, certainly, when it came to who had contributed. I know Ray had some quite heavy legal sort of fights about getting just rewards and stuff. But I think in the end, if you look at what’s happened with LADYSMITH BLACK MAMBAZO, I mean its put them on the map. I think initially everybody though ‘OK, that’s it, that’s the floodgates opening, we’re gonna have this deluge of local talent flooding the world markets’ and stuff like that - and it didn’t happen.. Ja, there was some exploitation, I mean let’s face it, but (a few of) the guys (involved) have certainly benefited from it, as well. So I don’t know, I wouldn’t like to get a whole moral attitude (about it now).

(Why was music of the 80s was so successful and why has it been largely forgotten?)

The biggest tragedy was that the archiving system was chaotic. And a lot of the multitrack masters got wiped. And burnt – EMI had a huge fire, I think it was in the early 90s. I know also that a lot of the Gallo multitracks were recycled, they’d say, ‘OK, its released, so we can wipe those multitracks.’

You know, it’s part of the heritage that we have from South Africa, of the culture. But it was never recognised by the government of the day. A lot of it was kind of looked at as subversive, or to keep the masses happy. I don’t think that people really realised the potential of the songwriting in those days, and the performances. I mean that was…. the early days of those synthesizers and the drum machines and things like that, but there was still very much a performance-orientated mentality to it. I think also the songwriting was approached in a different way, there was a lot of buzzing going on in the studios, but there was a lot to write about. There was a huge amount of playing with concept ideas, the lyric ideas, to be subversive but not to be apparently subversive.

(What are you doing these days [2009]?)

I’m still working in studios. I do predominantly a lot of DVD productions. We shoot live shows, various acts. We did HHP this year. We did JOYOUS CELEBRATION. I do sometimes get involved with the visual guys, but I’m not a visual person. I’ll actually project-manage it, and put guys in whatever (roles). and we do a consulting thing with a big studio in Durban, a government-funded thing, they wanted a top-flight studio director. It’ll actually be up and running this week. It’s been the last sort of month and a bit. But it’s fun.

And then we’ve got some … I can’t even give you any details, because I don’t know too much about it. but there’s some big international producer who’s coming out to do a collaboration with some local producer.

You know, what’s kept me going is the technology. I love the technology. And the changes. I really embrace that.

For me, the late 80s and early 90s period was when I got involved up at Bop Studios, when they first started up. And that’s where I kind of probably lost track of what was happening in the local industry. I was doing a lot of stuff with…CAIPHUS had come back at that point, so I did a long project with him … and I mean the early 90s I was pretty all up in Bop, that was just…. you know, from studios here which had started to become really dated, it was this 10-year quantum leap into technology. I mean they were the top studio, it was all suddenly digital multitracks ... But I didn’t go through a period of that growth. It was just from here, cranky old 24 tracks and all that, and into what’s happening in LA right now (at Bop).

A couple of us, DAVE SEGAL is one of the other guys, embraced it. He went up there (Bop) all the time trying to do projects. He’s now with EDDY GRANT. He was LUCKY DUBE’s engineer – he did all the albums, he did all the live shows. So the band’s been picked up by Eddy Grant, and they’re touring now.

© Afrosynth